Media Anthropologist, Gabriele de Seta (Hong Kong) interviews Netize.net curator, researcher and artist, Michelle Proksell (Beijing) about her NewHive collection, the popular Chinese app WeChat, her 10,000+ image Chinternet archive, selfies and surveillance. June 2015.

Gabriele de Seta: So, starting right on topic: how is your relationship to self-portraiture? Do you remember the first time you took a picture of yourself?

Michelle Proksell: Well, I was originally self-taught in photography and later studied it further at University – working a lot with portraiture at that time. But to be honest, I can’t really remember when I first took a self-portrait of myself, except that I know it was definitely not a digital image because I was using film in the beginning – so there was no deleting option. The images had to be very well-thought out before using the camera’s self-timer. This action is so much different from what selfies have become in our culture now.

When I was a young teenager experimenting with photography, I remember being mostly fascinated with the objects in spaces and how that defined people’s lives. I felt like these “things” and “surroundings” were insightful representations of a person’s life and times, maybe even more telling than just an image of them. So in the beginning, before I ever took self-portraits, I was photographing things around me in my life, objects in my room and spaces around my house. I suppose they’d just be considered documented still-life or something, but to me, at the time, I saw them as an extension of myself – something closer to a kind of self-portraiture, without the body present. So in fact, maybe closer to what it really feels like to consider what remains after we pass. Because ultimately, selfies, as we know them now, have become about the living and sharing in real time, but portraiture and self-portraiture in the beginning, historically, is much closer to being about the dead – a documentation of a life once lived – singular images physically left behind, not data collecting on our hard drives, social media sites or in the cloud online. But don’t get me wrong… I’m a bit of a selfie whore myself now…. I have no problem adapting to the times. But my roots are originally analog when it comes to this stuff.

GS: What is this NETIZE.NET series about? The pages show a clear artistic intervention on your part, but where do the graphic elements come from? Is there a larger narrative or historical context behind them?

MP: This Netize.net series is made from content I’ve collected in WeChat (Weixin 微信) over the past year or so (since April 2014) when you and I started doing research together. WeChat is basically China’s homegrown OS and now most of the country uses it to conduct business and social affairs. I use a function within the app called “People Nearby”, which uses the device’s location-based services to collect content from people around me, within a 1,000 meters radius. At this point I have been able to amass around 10,000 plus images so far, exploring the public posted moments and profile pictures of strangers nearby me in a couple of major cities in China.

Initially, the focus was just collecting selfies, but as I was collecting them, I discovered this whole other universe within WeChat, so I quickly expanded the content I was collecting to anything and everything I could find relating to memes, digital graphics, trends, fashion, photography, texts and other artifacts of contemporary Chinese online culture. The act of collecting this, often through screenshots, is keener to documentary photography than anything else though. It’s me, on the network, documenting what’s happening around me in real time – a kind of collection of localized small data. This kind of imagery not only helps give me a clearer picture of the culture here, but also reinforces my understanding of the localization of the Internet and networks and how physical it is to all of us.

My artistic intervention is trying to contextualize this content in a new way on NewHive for Netize.net, which basically just functions as a platform for the content to exist outside of the archive and outside of WeChat. It allows me to share this content thoughtfully with audiences outside of China, within a more relatable context. Which is where the research for Netize.net becomes so vital to understanding all of this. What is the online culture here in China? How is that influencing artists? How are artists using it in their artworks? How does that reflect on the bigger picture of contemporary China? My research of Chinese artists and net culture for Netize.net is just an extension of my practice as an artist, using and collecting content for my Chinternet archive. This particular collection for Netize.net has just become one of many forms the archive is taking on.

GS: This series of pieces you put together for NETIZENET is clearly concerned with self-representation online – not only selfies but generally visual elements from Chinese social media platforms. What have you learned about China through the lens of is this ongoing collection of vernacular content for your daily relationship with China?

MP: The Chinternet archive itself is ever expanding and diverse, changing with the times, as quickly as culture is morphing around me, which I can actually see reflected in the content I find in real time. You can’t go anywhere in this country without running into people glued to their mobile devices. Most of people’s lives here are dealt through WeChat – business, family stuff, dating, friendships, hook ups, retail, online bill pay, sending people money, sharing contacts, phone calls, video chats, news, networking, sharing art, making art, getting a taxi, etc. – all within the confines of one app.

And with this kind of centralization of content and usage, the relationship to the mobile device, and thus the Network, feels much more extreme here than in parts of Euro-American online culture(s). I find that juxtaposition of the physical world around me and how, where and what people are posting to be most interesting because it’s unlike any other social network I have seen before.

It’s a much smaller network of internal contacts than the traditional Web or social media sites we think of in the U.S., or even in the rest of the Chinese Web for that matter, which are typically accessed through big sites like Weibo, Youku or Baidu. WeChat is not a search engine; its people’s real lives posted in real time. The “People Nearby” function I use to collect this content is what opens up that network. It allows me to see what some people do want to share publicly, even to strangers online. And that allows me to understand what is happening culturally and economically within the physical context of China.

In the beginning…. when I started collecting this content, it didn’t take long before my daily subway rides in Beijing became even more interesting. I had sifted through and collected so much content just within the first month of starting this archive that I was able to sit on the train, look at the strangers around me and pretty accurately guess where they might live, what they might do for work, what kind of selfies they would take, etc. – just based off of hours and hours of looking through people’s public posts. The objects in the pictures, the viral graphics, the promotional materials, the beauty products, the news articles, comments of their daily lives, the ways they posed in their selfies, the clothes they were wearing, pictures inside their houses – these details were discoveries that became clues to understanding better who was around me on the train. That really changed my perspective of China in a new and fascinating way. I suddenly felt closer to everything somehow, even as a foreigner. I have been able to see the intimate reality of a part of China I would not be able to see otherwise. It’s very hard to relate what exactly that means on a personal level though. Because it’s more of a feeling than a defined understanding—I have begun to realize better what the differences and similarities between cultures really mean and how that applies to the real world. It’s made it easier for me to adapt to China and to get closer to my Chinese friends and the artists I work with. The images I have collected are merely artifacts of the contemporary culture here, happening in real time.

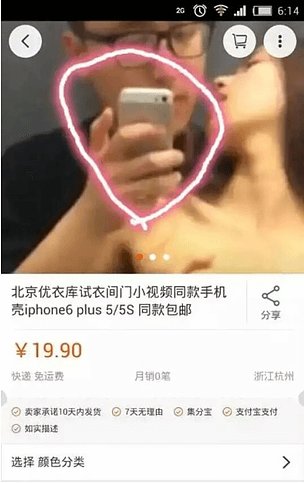

Many sellers use photo editing apps like this to edit their selfies with comments, product slogans or highlight areas of the face or body that the product is intended for. In the case of this particular selfie, the seller is trying to show the whitening difference this product can offer. Michelle’s current Netize.net collection also uses similar editing aesthetics from the same photo editing tools.

GS: Before talking about the relationship of your WeChat collection with local artists, I’d like to hear more about what you think about Chinese Internet culture. Do you notice any major trends among these images, or any local specificity that clearly separates Chinese online culture from the American one?

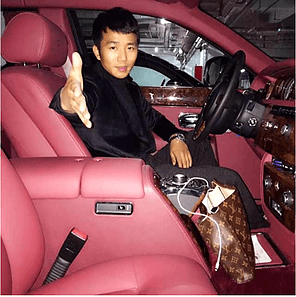

MP: I would say the most striking difference is the speed at which information trends and circulates, mostly because of an app like WeChat and the role of the smartphone. My understanding from the last three years of observation here, is that at this point in China’s digital online history, the internet really exists in people’s hands. Chinese branded smartphones like Xiaomi and Huawei, plus reasonably priced phone networks have made accessibility that much more affordable. I have images in the archive of migrant workers, farmers, rural city life, urban life, retailers, business men, fancy cars, elaborate home interiors, piles of money, young teenagers, old people, mothers… basically revealing the demographic diversity of users online – for many of who the first access point to the web was probably through their smartphone, not a computer. This is very different from what we are used to think about the Internet: in the U.S. and Europe, most people first accessed the Web through a computer, which was incredibly expensive and meant you had to be of a certain demographic to afford to access and use it in the beginning. Even today smartphones and data plans are still relatively pricey in America. Whereas here, migrant workers or poorer people, as well as the wealthy and growing middle class, all have similar ability to access the web through affordable networks and devices.

This means easy access all the time. You can still make phone calls and get online even on the underground subway here. So at any given point that something starts trending, the ability for it to circulate through Weibo, QQ and WeChat apps is unstoppable. It’s like a wild fire… I think the recent Uniqlo x-rated video madness is a perfect example of this: I would say, according to my experience, that it was probably the fastest trending thing I’ve ever seen circulate on the Chinese web so far. It gained momentum in less than 10 hours of its upload and the height of its circulation existed mostly within the first 24 hours. I’ve never seen something explode on the web that fast and be able to witness its lifespan in real time the entire duration, moment by moment. And even more recently on August 3rd, 2015, the rainbow phenomenon, or happening, which consisted of a flood of sunset and rainbow photos feeding through people’s moments in WeChat, mostly through Beijing networks, only lasted as long as the sun was setting. That made that meme particularly fascinating because it was so localized and time specific to a physical phenomenon happening outside. We hadn’t seen the sun in quite some time at that point… so we were all sharing in this glorious moment of rainbows and sunset. It was fantastic. What shocked me more though, was by the time the sun had actually set (maybe within two hours max), a commemorative gif animation of Mao with shooting rainbows out of his eyes and into the sky was already circulating in chat groups – somehow officially marking the phenomenon as a meme.

I think the constant access most people have in China just allows this to happen in way I have never seen happen in the West. When American artist, Ben Aqua, made that popular T-shirt some years ago that said “Never Log-Off”, well, I think that concept really applies more to China now. It often feels like no one ever logs off here. To me that seems almost futuristic. As if we are embarking on something we could call Web 3.0 – total integration of the web into our life, body and soul.

GS: You mention how the ongoing collection of content posted on WeChat allowed you to get much closer to everyday lives of Chinese people and changed your perspective of China. This practice seems very close to street photography or even voyeuristic photography, since you prove the public profiles of people in your vicinity without engaging with them directly, and save their personal expressions into a larger body of material. How does this approach relate to your own artistic practice, and what kinds of understandings did it bring you closer to? Is it also a commentary on how much voyeurism and social surveillance are deeply embedded in our use and the success of social media?

MP: This may sound strange, but my relationship to China now is really influenced by my early youth in Saudi Arabia. I was a foreigner there too – as a young American child in the 80’s before social media or even reliable overseas phone calls… so you can imagine the kind of stares you grow up getting used to, and even the level of acceptance you gain for surveillance – because that’s all you know. My parents have stories about our phone calls being monitored and they even taught us kids at an early age what could be said or done in public spaces, and what couldn’t. This extended to our travels throughout Asia too. So my early childhood was full of a kind of paranoia for being monitored as the foreigner. Strangers all over Asia were taking photos of me and staring at me when I was young. So, now as an adult, I expect to be observed, especially in a place like China where public space is the most common space to engage in. In fact, I think someone is quite ignorant, no matter where they live in the world, if they don’t think they are being monitored to some degree. The most obvious tangible examples of this are surveillance cameras nearly everywhere in modern cities, not to mention the uncannily tailored suggested pages and ads in Facebook.

That being said, when you play the role of a foreigner in any situation there is a certain degree of sensitivity you have to always keep in your constant awareness. Self-censorship should be a part of everyone’s consciousness now, because voyeurism, just like surveillance is commonplace and expected. It’s not going away either. The careful balance is to not let paranoia overwhelm you. And that’s where my relationship to the Chinese web and people is so vital to my experience here.

I really enjoy being in China right now and there is a special kind of energy in the way things are so quickly and interestingly developing. With the intense speed at which things are changing here, it actually feels more open in some ways – like the Wild West must have felt at one point, which I think people who have never been here really can’t understand. My role as an artist is that it lets me get close to the underground and get to know how the culture is developing side-by-side with the technological devices we are all so dependent on. In the beginning of collecting for this archive, I did try to engage with people around me, but found that men only wanted to talk about how beautiful I am and women would only talk to me if they were selling me things, or some people just wanted to practice their English once they found out I was an American. I’ve tried recently to attempt to start conversations again, and the same thing happens. So most of the conversations I have about the trends are with Chinese friends and artists I already have relationships and collaborations with.

And to be very clear, with this project I am not commenting on the deeper darker aspects of voyeurism or surveillance, I am looking at the exciting development of the social network and how everyday people are engaging with that. I am curious to see how the network influences the real world around me and vice versa, especially in how trends and memes circulate. This body of work, with the archive, is collected so that I can genuinely begin to connect and understand this contemporary China around me, which fascinates and inspires me everyday. Western media really loves to dwell in the “weirdness” of Chinese culture, whereas I am more interested in sincerely connecting to it and trying to understand the roots of its differences. Because ultimately, “why” we are using these online tools are very similar across cultures, the major differences are in “how” we are using them. I’m interested in the “how” part of things more.

Therefore, the active documentary style collecting of content from WeChat has made me feel closer to China because I have been able to see where the content is coming from first hand. I get to attach real people to the trends. I get to visually connect the dots and begin to see how things are emerging. Comments people make in their own postings also put things in their words, not mine. And so, the “why” part of things is something my Chinese friends are so vital for me to understanding all of this better. And because of this, I rely on their confirmation and explanation to my questions, and therefore my relationship to the language and to Chinese people gets stronger too. I can’t begin to understand this content without also having in depth conversations with Chinese friends and artists to reveal what, where and why things are as they are. I look at this project as a bridge between cultures, because on one end I am able to help document Chinese digital culture as its emerging in real time for China’s longer term online history, and on the other end, Chinese people can help me (and my Western background) begin to connect better to China, in hopes of sharing that experience with others.

媒体人类学家胡子哥Gabriele de Seta(香港)采访网友网馆长、研究者、艺术家媚潇 Michelle Proksell (北京)关于她的新NewHive系列、微信、她的一万多图片中国互联网档案、自拍和监视。2015年6月。

胡子哥:自拍照对你来说是什么?你是否记得第一次拍摄自己的照片是怎么样的?

媚潇:最初我自学摄影,后来在大学继续进修——当时拍摄了很多肖像。但是说真,我已经不记得第一次拍自拍是什么时候的事情了,但是它肯定不是数码图像,因为当时我实践的是胶片摄影,所以没有“删除”的功能。每按一下自动定时器前都必须想好照片的每一个细节,这跟我们现时所理解的“自拍”很不一样。

十几岁的时候我开始在摄影这个媒介进行实验,我记得当时对在不同空间里所存在的物件,以及它们如何表现这些人的生活细节特别感兴趣。我觉得这些物件和其周遭环境都能给予关于一个人的生活及时代一种具洞察力的表现,也许比一张单纯的肖像更有叙述性。所以在那个时候,在我有任何自拍的经验之前,我都一直在拍摄我身边的事物、我自己房间里的物件及我家里不同的空间。也许它们会被视为一种静物的记录,但是对我来说,当时它们是我自身的延续——一种类似自拍但没有

身体在内的图片。其实,它们有点像是对死后的一种想像,因为我们现时所理解的“自拍”基本上是活着的人之间的实时分享,但是肖像和自拍照/自画像在最初,在历史的角度上来说,是更与已逝去的人相关的:它是摄影师对曾经活过的生活的一种亲身记录,成为了被遗留下来的图片,而不是我们在自己的硬盘、社交网络或云存储里收集的数据。但请不要误会我的意思…我其实也是自拍控…我很乐意适应于时代,只是就技术的层面来说,我的背景是胶片摄影。

胡子哥:这一组给“网友网”创作的图像的意义是什么?它们明显地有你的个人艺术性介入,但是这些图形元素的来源是什么?它们背后是否有更广泛的叙事性或历史性语境?

媚潇:这一组为“网友网”创作的图像是由我在过往一年多

(2014年4月至今)的时间里,也就是我们俩开始一起做研究的时候开始从微信平台上收集回来的一些图片制作而成的。微信是中国本土设计的操作系统,现时国内大部分人都用它来经营生意和处理各种社交事务。我用这个应用程序里的“附近的人”功能:它运用电子设备的定位功能搜索离我一千公里半径范围内的人,令我能访问他们的个人页面。到目前为止我已经在国内数个大城市收集了一万多张在公开的朋友圈里发布的图片,以及陌生人的头像。

最初我更专注于收集自拍照,但是在过程中我发现了在微信平台有它的独特世界,所以我迅速地扩展了收集的范围至任何及所有我能找到跟迷因、数字图形、潮流、服装、照片、文字等与当代中国网上文化相关的资料。我一般用截屏的方式收集这些图片,其实这样更接近于纪实摄影。因为在这个过程中,我在线上实时记录在我身处的周遭所发生的事物——是一种地域性的数据收集。这些图

片不单更清晰化我对当地文化的理解,同时也令我更了解互联网本身的地域性及物质性。

我的艺术性介入其实是希望能用新的方式把这些素材呈现于托管在NewHive上的网友网,它基本上是存在于我的资料库及微信以外用来展示内容的平台,同时也令我能够思虑地在适当的语境里向西方分享这些内容。也是因为这样,我为网友网所做的研究才会对这一切的理解提供重要的洞悉。这里的网上文化是怎样的?它怎么影响到这里的艺术家?他们如何在实践中运用这些资源?这种趋势如何反映到当代中国更广泛的语境?我为网友网做的对中国

本土艺术家及网上文化所做的研究只是我身在中国作为一位艺术家的身份的一个延续,为我建立的资料库使用及收集资料。这一次为网友网创作的系列也只是我的多种资料收集的其中一种模式。

胡子哥:你在这一系列的图片中很明显在试图探讨在线的自我表现——不只是有关“自拍”,但同时涵盖了中国社交平台中出现的视觉语言。通过持续地收集与你自身跟中国之间的日常关系相关的地域性资料,你对中国在哪些方面有了更深入的理解?

媚潇:我的中国互联网资料库本身正在不停地扩展和变得多样化,与时代并进,赶得上我身边文化的变化速度,而这些变化,亦能在我实时收集的资料中清晰可见。在这个国家无时无刻都能看见手机控,许多人的生活细节都通过微信解决,包括各种业务、家事、约会、朋友、约炮、零售、网上缴费、寄钱、分享络、电话通讯、视频聊天、新闻、分享艺术、创作艺术、打车等等,一切尽在这个应用程序其中。

随着这些资料及其运用的集中化,这里与移动设备及网络的关系在某程度上变得比西方网上文化感觉更加极端。我觉得我身边的物质世界与这些人如何,在哪里,在发布什么内容的并置是最有意思的一部分,因为它与我接触过的其他社交网络不一样。

它是一个比西方传统互联网或社交平台,甚至比中国本地的,像微博、优酷或百度这种重要网站更小更集中的个人化网络。微信不是一个搜索引擎,而是一个人用于实时分享他们真实生活的平台。我用来收集图片的“附近的人”功能正是用于打开这种网络的工具,通过它我能看见某些人选择公开,包括对陌生人分享的内容,这为我提供了理解有关当下中国文化及经济情况的渠道。

自从我开始收集这些资料不久,很快就令我每天在北京地铁上的时间变得更有意思。在建立这个资料库的第一个月内,我就看过,也收集过许多的图片,这令我能够蛮准确地猜测到在地铁上这些人可能住在哪儿,做什么工作,他们的自拍照会是怎样的…一切通过不断地看不同人公开发布的内容。图片中的物件、图形、宣传资料、美容商品、新闻消息、对于日常生活的评论、他们在自拍照

里的姿势、他们穿的衣服、他们家里摆放的图片等——这些细节令我更理解在地铁上身边的人是谁。这给予了我对中国一种新的,更有趣的看法。虽然我是外国人,但是我突然之间觉得对一切有了新的认知。从此我能够更清晰地看见中国一部分的现实,但确实很难解释就个人来讲其中的意义,因为始终它不是一种明确的理解,而更是一种感觉。我开始更清楚不同文化之间的差异和相同之处背后

的意义,以及它们在真实世界中扮演的角色。它令我能容易适应于这个国家,同时也令我能更靠近我的本地朋友和合作的艺术家。我收集回来的图片只是这里实时发生的当代文化产品。

胡子哥:在我们开始谈论你的微信收藏与本地艺术家的关系之前,我希望能够多听你说说你对中国的网上文化的看法。你有否在收集到的图片中发现一些主要的线索,或一些令中国网上文化区别于美国网上文化的地域性因素?

媚潇:我觉得两者之间最为不同之处是信息被传递的速度,主要是因为像微信这种应用程序和智能手机在日常生活中所扮演的角色。就我过去三年间在这里的观察来说,目前为止在中国的数字在线历史中,互联网是存在于人的手里的。中国本土的智能手机,比如小米,加上手机网络服务费也不高,提高了网络的可及性。在我的资料库里有农民工、农民、农村生活、城市生活、商人、豪华汽车、特殊的室内设计、堆积如山的钱、年轻人、母亲等,透露了用户的异质性,其中大部分用户最初接触互联网有可能是通过智能手机,而不是电脑。这一方面与西方历史很不一样。西方人一般是通过电脑第一次接触互联网,而当时是非常昂贵的。就是说,那时候你必须是能负担这种费用的人才能使用互联网。而且智能手机和手机网络服务在美国依然很贵。但是在中国,无论是农民工或比较贫穷人,还是有钱人和快速增长的中产阶级人士,都能通过实惠的网络服务及移动设备使用互联网。

这代表了全天候的信息访问。这里在地铁上你还能打电话和上网,所以有任何热门话题的时候,你还是能随时在微博、QQ及微信上转发。就像野火一样…最近忧衣库的限制级视频就是一个很好的例子。对我自己来说,它是我目前为止见识过最快被流传的话题。在视频上传后不到十小时就开始变火,在二十四小时内达到了转发频率的高峰。我从来没有在网上见识过这么迅速传播的热门话题,而且见证了整个过程。更近期的还有“彩虹现象”或“彩虹事件”,那个时候在微信朋友圈里发现了很多日落和彩虹的图片,大部分的出现在北京的网络,一直到日落时间才停了下来。这个迷因因为它的地域性及时间性而变得特别有意思。在那之前我们已经有一段时间没有看过太阳了…所以大家才那么积极地分享彩虹出现和日落的美丽时刻。真的很棒。但是令我惊讶的是在天黑的时候(大概两小时内),在群里已经有人开始分享一个从毛泽东眼里向天射出彩虹的GIF,也在那个时候将这个现象变成了一个迷因。

我觉得因为在中国大部分人无时无刻地用手机,所以我才能看见这种在西方没有见过的现象。美国艺术家Ben Aqua几年前制作了一件写着“永不注销”的T恤,我觉得吧,那个概念现在来说更适用于中国。有时候真的觉得这里的人永远都放不下互联网。对我来说这是几乎未来主义的现象。就好像我们正在步入一种可以说是互联网3.0的世界——也就是互联网与我们的日常生活、身体和灵魂的一体化。

胡子哥:你提及到你在微信上持续地收集的素材令你更靠近中国人的平常生活,甚至乎改变了你对中国的看法。这种实践似乎很接近街拍或窥视摄影,因为你从来不直接联系这些素材中涉及到的人,但是你把他们的私人图片和文字储存至一个更大的资料库中。这种工作方式如何与你自身的艺术实践相关,它令你更深入理解到什么?这是否在评论窥视及社会监控其实与社交网络的运用及成功息息相关?

媚潇:这听起来可能有点奇怪,但是我跟中国现在的关系其实是有受我在沙地阿拉伯的童年的影响的。当时我也是当地的外国人——身为一个美国小孩在八零年代,在社交网络的时代之前,甚至在有稳定的国际长途电话服务之前… 所以你能想像我小时候会习惯被盯着看,还有在被监视下得到的接纳——这是我那时候所知道的一切。我父母提及到我们的电话有被监听,而在我们很小的时候他们就开始教训我们在公众场合有什么是能说、能做的,什么是不能说、不能做的。这一切一直延续至我们在亚洲的游历。所以说,我的童年充满着一种外国人被监控的焦虑。我小的时候在亚洲各地都有陌生人在街上盯着我看和拍我的照片,所以现在身为一个成人,我自然也有被观察的预期,尤其是在中国,因为这里的公共空间是最常用的空间。其实无论你生活在什么地方,如果你不觉得你随时都在某程度上被监控的话,我觉得你是蛮天真的。最明显的例子就是在所有现代城市到处可见的监控摄像头,还有在Facebook上那些不寻常地个人化的广告。

话虽这么说,在任何情况下作为一个外国人,你都必须保持某一程度的敏锐度和警惕。自我审查已经成为了在每个人的意识中必要的一部分,因为窥探就像监控一样,都是意料之中的事。而且它并不会消失。你只有不被焦虑的情绪把控才能得到平衡。也是因为如此,我跟中国互联网和本地人的关系才对我在这里的生活有这么大的影响。

我很喜欢我现在在中国的生活,而且这里有一种很微妙的动力,一切都在迅速而有趣地发展。因为一切的改变速度,所以在某些方面其实感觉它更开放——就像也许美国西部曾经经历过的,没有亲身来过的人就是没法理解。身为一位艺术家令我能更靠近地下文化,更深入了解在发展中的文化,以及我们所依赖的科技。刚刚开始为资料库收集素材的时候,我其实有主动跟这些陌生人沟通过的,但是发现一般男的只是想调戏我,而女的只会因为想推销产品而跟我聊天,或当某些人知道我是美国人的时候就只想

跟我练习英语。我最近再次尝试了跟其他陌生人聊天,还是遇上这种情况。所以有关热门话题的对话都是跟我自己现有的中国朋友及合作过的艺术家发生的。

明确地说,我其实没有想过通过这个项目去探讨窥视和监控的黑暗一面,我只是在观察社会网络有趣的发展,以及本地人日常的运用。我好奇这些社交网络如何在影响我身边的真实世界,反之亦然。尤其是热门话题和迷因被传播的速度。这一部分的工作和这个资料库,都是为了我能真诚地去理解令我着迷同时也每天在激发我的当代中国。西方很喜欢专注于中国文化“奇怪”的方面,但是我更是希望能真诚地与它建立一种关系,去理解它的差异性。

我们“为什么”运用这些在线工具,基本上是没有文化上的差异的,最主要的区别在于我们“如何”运用它们。我对这个“如何”的部分更感兴趣。

所以说,我从微信平台上的纪实性资料收集令我觉得更靠近中国,因为我能第一手知道这些内容的来源,我能把真实的人直接联系到这些热门话题上,我能理解其中的关联而开始注意到新兴的话题。这些人在他们自己发布的信息上留言和作出回复,这些都不是我自己做的假设。所以说,我的本地朋友在我对“为什么”的部分的理解上扮演着重要的角色。也因如此,我依赖他们对我提出的疑问的确定和解析,也之所以我跟这里的语言和人的关系也日渐拉近。没有我跟这些朋友和艺术家的交流,我对这些内容的理解也不会很深入,他们会跟我解释这些是什么,它们的来源及它们形成的原因。我视这个项目为一种不同文化之间的桥梁,因为在一方面我有助于实时记录在发展中的中国数字文化,另一方面本地人(及我的西方背景)能够帮助我开始与这个国家的文化产生关系,我亦希望日后我能分享这些经历。