The Chinternet Archive

Field notes on location-based features, Chinese online user behavior

The following summarized field notes are just a few of the main observations and reflections I have developed as of 2016, while independently collecting digital artifacts from the Chinese Web since 2014. These digital artifacts were acquired as empirical content for an ongoing archive called, the Chinternet Archive. This content was extracted through active use of the Chinese app, Wechat, or in Pinyin known as Wēixìn and in Hanzi known as 微信 — “micro letter.” The online fieldwork involved with collecting, dissecting, organizing and concluding the relevance of this content was influenced by living and working in China, conducting interviews with Chinese locals, continual independent research of China’s internet history, studying Chinese language and culture at Tsinghua University and conversations with my research partner, media anthropologist Dr. Gabriele de Seta. The Chinternet Archive has taken on many forms since its inception, including academic publications, lectures, interviews, art installations, online real-time performance as time-based art, photographic prints, and has been exhibited at a number of online and offline exhibition spaces.

An introduction to the Chinternet Archive:

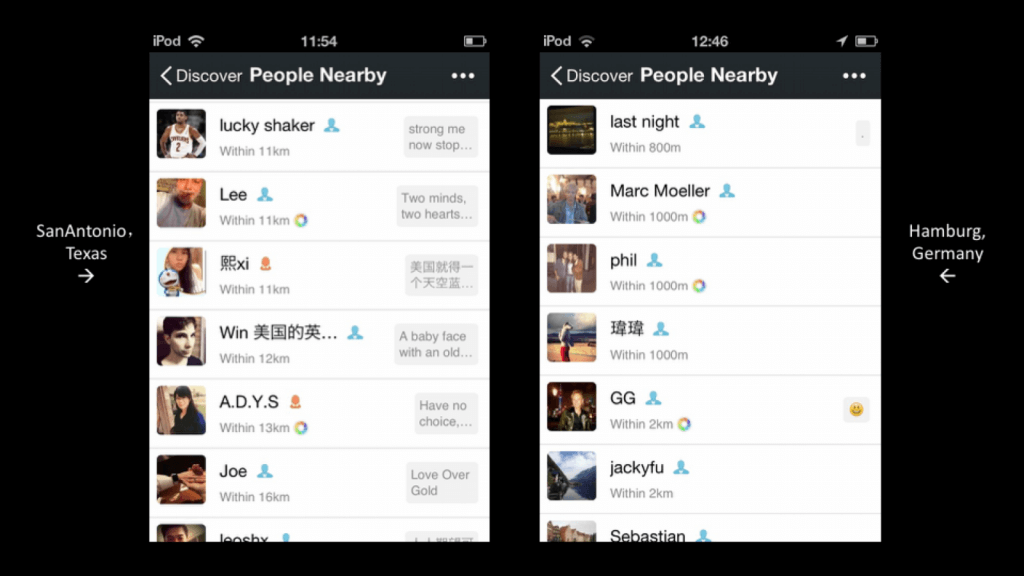

Within the popular Chinese app WeChat there is a function called “People Nearby” that allows users to access the phone’s location based services to connect to strangers who have also activated the same feature within a 1000m radius. If users decide to keep their accounts open and public for strangers to explore, then onlookers activating this feature can see up to ten posts they have recently made. It is through this feature that I have been collecting 40,000+ images, .gif animations and videos for the Chinternet Archive (as of August 2016).

The collection still continues to increase daily. I began collecting this content from mainland China in April 2014, at first only curious about researching the aesthetics of Chinese-specific selfies. As the collection grew, so did the kind of content I collected. The archive itself now reflects on things such as nationality, identity, politics, memes, trends and the varying demographics of contemporary Chinese people. I have collected images in a number of urban Chinese cities including Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, Xi’an, Yangshuo, Harbin, Guilin and Hong Kong. In addition, I have also collected content from various cities and countries outside of China including Korea, Malaysia, Taiwan, America, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, Belgium and Holland (as of August 2016). Each city reveals its own digital history and localized characteristics represented through the users who are posting. On average I collect anywhere from 10 to 100 pieces of content daily at any given location I may be in.

The purpose of focusing on WeChat specifically, as opposed to other Chinese social media platforms like Weibo or QQ, is that most things relevant to representing the major trends of the Chinese web and user-ship these days are funneled into WeChat eventually. This most likely occurs as a result of WeChat being China’s first “homegrown OS” and platform that’s been truly international in a way that Weibo and QQ have never. Anyone who trades with China or who has family or friends residing there primarily use WeChat to connect, share and do business. For this reason, the content collected from WeChat not only represents common themes on the Chinese web but also personifies and reveals the growing economic and cultural influence China is contributing to the world presently.

Location, Location, Location:

In discussing what the Chinese internet is today it is necessary to acknowledge that it is a digital landscape with certain loosely defined ‘borders’ and Chinese characteristics influenced by its physical location. These ‘borders’ are merely the edge of what we in the western world might perceive as a kind of chaos or limitation merely because we don’t always understand the extent of it all or may never have experienced forms of online censorship on a day-to-day basis. However, the Chinese internet in the context of China is not necessarily chaotic or entirely limited per say in the eyes of locals. Instead, it is merely a digital mirroring of the vibrant social and economic activity developing in China on the ground level for the past few decades.

The Chinese internet exists as a kind of parallel world to the rest of the World Wide Web. What this means is that information and usage is specifically localized and emerges from the needs of its users. In comparison, the Chinese internet and the rest of the World Wide Web are distinctly different paradigms. Depending on the platform, use and location, sometimes one network is more efficient than the other. Instead of Google there is Baidu. Instead of Facebook or Twitter there is Weibo and QQ. Instead of Ebay or Amazon there is Taobao and Alibaba. Instead of Youtube there is Youku. Instead of WhatsApp there is WeChat. Some of the advantages of the localization of the Chinese internet have driven the development of extremely efficient shopping websites like Taobao or even more recently popular social “micro letter” software like WeChat, which is now beginning to emerge across the globe. The borders that we understand to define the uniqueness of experiencing the Chinese internet are beginning to be globalized slowly in some ways because of the mobility of Chinese social apps and the world’s focus on China’s development – thusly, influencing internet experiences around the world.

A brief look at accessing networks in China:

Because of the extreme speed at which everything is changing in China, both in real life and online, the lifespan of online content is much shorter than what we may see in other western contexts. Because of an app like WeChat and the role of the smartphone in China’s internet history, it’s very apparent that at this point in China’s digital culture the internet exists mostly in the hands of the people. Chinese branded smartphones like Xiaomi and Huawei, plus reasonably priced phone networks have made accessibility that much more affordable and expected amongst online users in China.

Some images represent rural city life, urban life, fancy cars, elaborate home interiors, piles of money, basement dwellings, factory dormitories, and squalor—effectively revealing the demographic diversity of users online in China, many of whom their first access point to the web was probably through a smartphone, not a computer.

This is a very different history from what we are used to thinking about the Internet in North America or Europe where the majority of early users first accessed the Web through a computer. At the beginning of internet user-ship in the West, networks were incredibly expensive which meant you had to be of a certain demographic to afford to access and useit. Even today smartphones and data plans are still relatively pricey in America and other European cities comparably. Whereas in China, migrant workers or poorer people, as well as the wealthy and growing middle and upper classes all have similar ability to access the web through affordable networks and devices. That means easy access for nearly everyone all the time, even on the underground subway system (literally all the time).

In addition, early internet history in the West included sometimes extensive waiting periods to access networks or load webpages. This experience most definitely influenced the early expectations and surfing experiences for many adults in western centric cultures. However, in China since many new users of varying ages in recent years have accessed the internet first through mobile devices, early online experiences and expectations of accessibility and the speed of networks are inherently different.

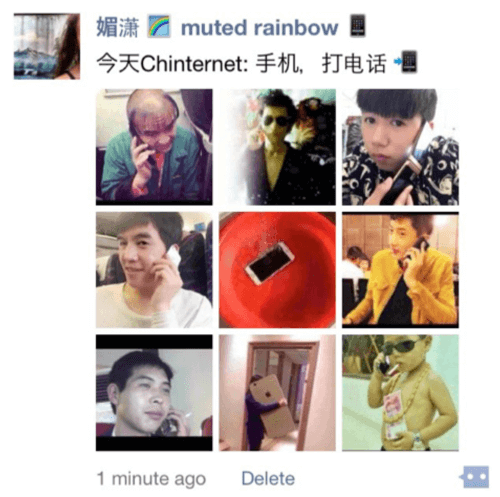

Posting habits and the lifespan of memes and trends:

Contrary to some western perspectives, the Chinese internet is not a desolate landscape but is, in fact, is full of insightful and culturally specific memes and trends that circulate expansively for the same reasons creative memes develop and spread in any other internet landscape. The mobility of smartphone apps from Weibo, QQ or Wechat also offers users an immediacy to share content by first documenting and broadcasting, then reflecting, creating and finally reacting and discussing what is happening in the real world at a speed I have never seen in the West before. This is mostly because of China’s unique mobile internet history, relatively reliable 3G and 4G networks, plus the abundance of WiFi access points in cities across the country and affordable handheld “hot spots” people can carry around with them.

How things are posted on certain platforms can bypass some aspects or forms of censorship also. A Weibo posting of an image or meme is inherently more public than a WeChat ‘Moment’ (publicly shared content) because of the differences of the platforms. WeChat is a relatively closed network of friends and personal contacts, whereas Weibo is more open and searchable of its users and topics. This ultimately contributes to determining the kind of content shared. For example, what might be posted openly in Weibo first will probably be a little more subversive and self-censored to avoid being taken down too quickly or entirely. In contrast, something posted initially in a WeChat group chat might be more explicit, regardless of what censorship might usually exist for the content, merely because it’s being posted within the confines of a semi-private feature of the app. All of this contributes to a vibrant digital experience in China and directly influences how content gets popularized.

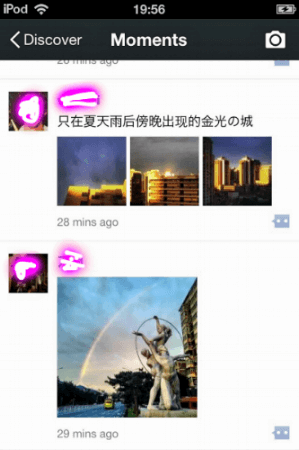

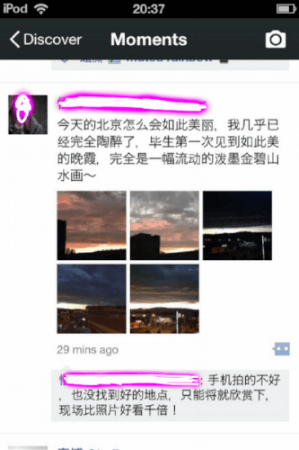

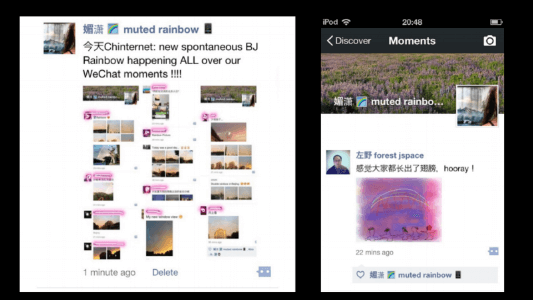

In addition, memes come and go as fast as the sun sets sometimes. For example, on August 3rd, 2015 a photographic rainbow phenomenon swept across the feeds of people’s WeChat moments, mostly through Beijing networks where the weather event was happening in real-time. Beijing hadn’t seen the sun in quite some days due to excessive smog over the course of a few weeks. So, in the emergence of a beautiful rainbow in real time, the whole of Beijing was photographing and posting about it instantaneously. Because of the location of the happening being based in Beijing, the nation’s capital, the meme had nationwide influence and appeal and ended up in WeChat Moments around the world. Anyone who had Beijing based people in their personal networks witnessed it. More shockingly though, was by the time the sun had actually set and the sky was dark, in about an hour or so after the initial postings, a commemorative .gif animation of Mao’s face in front of the Forbidden City with shooting rainbows coming out of his eyes and into the sky already began circulating in chat groups. This somehow officially marked the phenomenon as a meme. The circulation and posting of rainbow images slowed and ceased altogether once there was no light left in the sky.

This specifically shows the deep relationship these posts and trends have to time and location-based experiences in China. This ultimately reflects further on the close ties of perception people share for their real life and online life simultaneously.

Online life a reflection of real life and the Web’s potential future:

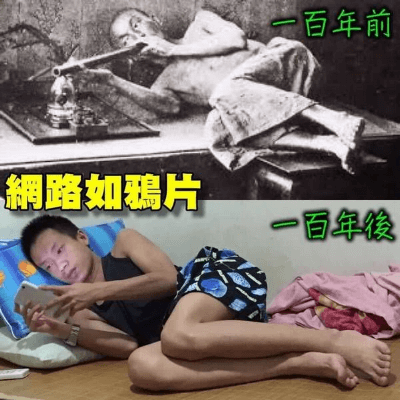

What the Chinternet Archive has revealed to me most about the bigger picture of contemporary China online is that mobile technology has a prominent role in the lives of the majority of Chinese people, despite income disparity. That will only continue to expand more as networks and forms of mobile technology expand throughout the country. It’s impossible to go anywhere in China without running into people glued excessively and exclusively to mobile technology.

Much of people’s lives in major cities are dealt through WeChat. This includes business, family affairs, dating, friendships, hookups, retail, online bill pay, prostitution, sending people money, sharing contacts, ordering food, playing games, making phone or video calls, reading the news, networking, sharing photographs, videos or selfies, getting a taxi, having a digital boyfriend or girlfriend, arranging appointments, booking doctor visits, using a digital secretary, etc. This interaction all occurs within the confines of one app. With this kind of centralization of content and usage, the relationship to the mobile device, and thus the network itself, seem much more extreme than in other parts of Euro-American online culture(s). The juxtaposition of the physical world and the digital world act as an extension of each other. For this reason and the concentration of so much information and online activity, WeChat as a platform could potentially represent the next phase of the Internet.

With Web 1.0 we saw the introduction of BBS boards, email and a certain level of graphics. With Web 2.0 we saw the emergence of social networking sites, online marketing, big data analysis and the advanced development of WiFi and cellular networks. With Web 3.0 we may not only see a new level of graphics, mobility, speed, and security but perhaps even more so, the development of centralized content used through mobile access points that could become directly a part of our bodies someday — completely immersive experiences on a day-to-day basis. American artist Ben Aqua humorously made a viral T-shirt some years ago that said “Never Log-Off”, but his concept really applies more to Chinese online users today more than ever before.

The increasing popularity of wearable technology, rapid VR and AR development within China’s tech start-up scenes, plus a culture enthusiastic to adopt the virtual world over the reality that actually exists, has opened the country up to expediting the development of technology for the sake of economic growth. These are perfect conditions for China to socially accept the internet potentially being a part of the physical body rather than just an extension of it.

My artwork and research with the Chinternet Archive reflects on a version of this reality. The mobile and the virtual world of China is quickly beginning to encompass and influence the user behavior and self-representation of contemporary Chinese people inside and outside of the country. Because of the growing global application of WeChat in other countries, this experience will only continue to expand across cultures, especially amongst developing countries with similar mobile internet histories and advancing network infrastructures similar to China.