GIFs and Trans-Cultural Expressions:

“As in any artistic subculture, there are those who produce spectacles that demand attention, and those who quietly go about their work hoping for a reflective viewer who will take some time to engage”

-Sally McKay, from the essay:The Affect of Animated GIFs

Nine Computer Exercises for the 21st Century Online Digital Interactive Era

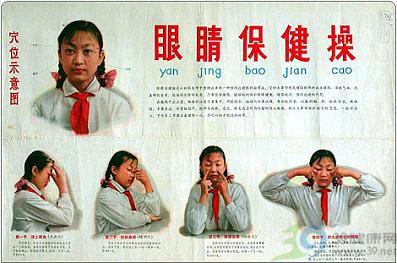

Practice, patience and exercise are ancient Chinese priorities for preserving wellbeing and are found in Daoyin health traditions. This includes martial arts or breathing practices, such as Kung Fu, Qi Gong and Tai Chi. The preservation of health in Chinese culture derives from daily physical exercises and breathing routines called Jiànkāng tǐcāo in pinyin or 健康体操 in Hanzi.

These routines have been traced back to the earliest years of Chinese culture and medicine and are still incorporated into today’s modern Chinese lifestyles. In most parks of

Chinese beliefs about health preservation and daily exercise are direct influences in

In the introduction quote found at the beginning of this essay, Sally McKay, an independent curator, writer and artist, says that there are those that need the spectacle, and those that create content in hopes of capturing a longer more engaged reflection of ideas (McKay 2009). This engagement requires a kind of patience that seems to run in contrast to our short-lived attention spans so prevalent in today’s digital and online cultures. Who has the time or patience to sit in front of one webpage for longer than a minute? And yet, with Nine Computer Exercises for the 21st Century Online Digital Interactive Era, Aspartime is asking us to do just that. Each webpage teasingly instructs us to participate with the screen and to meditate with the media. This is commentary on how the majority of online users tend to scan content rather than slowly focus or absorb more deeply.

Concerning the use of the GIF format on the Web and in Art

The history of GIFs in Net culture began at the onset of the development of the Web. Because of this, GIFs have an online timelessness and flexibility that allows them to play across browsers, platforms, operating systems and even online censorships. Authorities can block a site entirely, but would less likely target a specific format like GIFs, JPGs or PNGs to block from a site in an attempt to censor. Also, there is currently no easy way to tag specific controversial content found in the GIF format to prevent the spread of its online circulation. Therefore, in general GIFs constitute a kind of digital liberty that can be utilized for expression. It is a perfect format for sharing humor, satire and mockery, which is reinforced through the continuous loop the format offers.

In Sally McKay’s essay, “The Affect of Animated GIFs”, she mentions how this format appeals to artists because it signifies “an anti-corporate agenda as well as a kind of truth to materials commitment to technologies that are elegantly designed for democratic use” (McKay 2009). The GIF format has spread effortlessly across the Chinese web since its introduction and the onset of social media platforms within the country. The format has the same meme-like success found in any other part of the World Wide Web, a kind of cyclical symbol of cultural continuums. We all have an equal ability to see excerpts of content found in circulating GIFs. Even more so, we are often able to enjoy them with or without a cultural context.

The popularity of GIF animations across cultures allows a space and place for even Chinese artists to explore deeper conceptual ideas no matter how simplistic an idea or the format itself may seem at first. Chinese artists can engage in the same kind of digital dialogue you see across any other network, across language barriers and despite the onset and configuration of The Great Firewall. Aspartime’s use of the GIF format follows suit with previous artist’s using GIFs to forego the traditional approaches of exhibition. However, their reference to ancient Chinese health practices in digital form, their unique cultural background and the history of online censorship in their country seems to contextualize their work into a different chronology.

At this point in China’s contemporary art market, artists are pressured to produce objects solely for monetary consumption. Success is measured, expected and achieved almost entirely through the means of institutions or commercial spaces, often influenced either by Western perspectives or particularly traditional Chinese collectors. DIY practices and Internet Art are less recognized genres in the bigger picture of the contemporary Chinese art market at this point in it’s history (as of 2015). This perpetuates an external pressure for Chinese artists to still produce Chinese looking art in traditional formats and presentation. But there has been a shift emerging in the next-generation of Chinese artists who are redefining and challenging what it means to create contemporary Chinese art. This has also given space in the last years, since 2014, for alternative artistic genres to gain attention.

An exhibition during the month of November 2014 in Paris, France at the Palais de Tokyo Gallery, challenged this notion “without a Mao-inspired or Cultural Revolution stylistic cliché in sight” (Shaw 2014). This exhibition was one of the first to highlight Chinese artwork that did not look particularly Chinese. Philip Tinari, the director of the Ullens Centre for Contemporary Art in Beijing, was quoted saying: “Young Chinese artists making work that does not look recognizably Chinese is perhaps the biggest trend of the past few years” (Shaw 2014). Living between multiple countries often influences Chinese artists as well. Aspartime currently resides between Beijing and London and they openly describe how both the Western and Chinese internet have influenced their work.

The collection of interactive GIF animations Aspartime has created for Netize.net are able to by-pass the museum and gallery system altogether to produce for a larger public audience outside of The Great Firewall and China itself. This is not a new idea or use of the GIF format that doesn’t already exist in the longer history of art produced for the Internet. However, in the context of China this is most definitely a profound gesture and allots an opportunity for Chinese artists to produce and expose their art for themselves, by themselves, for the world, outside of expectations imposed upon them by the traditional Chinese art market as it currently exists. This medium allows Chinese artists a new playground for expression and the use of the GIF format is a particularly autonomous way of doing so.

Concerning online trans-cultural expressions:

With a transformation of un-recognizably Chinese artworks emerging by Chinese artists and foreign artists using Asian content in their own artworks, a deviation in source of content and user background seems to be swaying across all borders. What does it mean to produce or appropriate culturally relevant material in the age of the Internet?

The use of the Internet to share GIF animations, as well as content derived from different parts of the Net to create them, is a very present example of the trans-cultural trends that have been surfacing across the world in other mediums as well. If nothing else, what the Internet can offer us is a glimpse into the aesthetics of other popular cultures, subcultures and histories with the ability to appropriate these images, video and sounds for ourselves. The origin of the Internet is based in connecting and therefore is the perfect platform for cross-cultural expressions—stripping our initial assumptions about the starting point of influences that contribute to cultural-specific aesthetics or content. If there is anywhere in the world where all cultures have some trace of existence and relation, it’s the Internet. Advancements in communication tools and applications only strengthen this online aesthetic globalization.

Nine Computer Exercises for the 21st Century Online Digital Interactive Era doesn’t look particularly Chinese nor should it. The collection has appropriated GIF animations from different popular cultural influences from other online sources. But put together, this Eastern and Western imagery re-contextualizes ideas about Chinese culture pertaining to patience, preservation and exercise that the West has been importing for centuries. Ove the years, this import has included acupuncture, meditation, forms of martial arts and even Chinese herbal medicine found in upscale health stores around the world, etc. Online cultures are no different in their ability to traverse different cultural landscapes. Aspertime’s collection reinforces how Chinese artists today are being influenced by Western digital cultures just as much as they are their own.

What better way to reflect on this than through a “silly” but thoughtful representation of exercise in the form of an interactive online game. The cyclical looping of the GIF format in this collection provides the conditions for us to sit in contemplation as well as to test our patience. Aspartime welcomes us into a kind of awareness perhaps, reinforcing the reality and implications of how our digital era impacts our daily actions, attention spans and perceptions.

– Michelle Lee Proksell 媚潇

Written in 2015